Putin's political calculation on Ukraine and why western sanctions only play into his hands

The discussion on why Russia may invade Ukraine often centers on the strategic threat Russia would face if Ukraine joined NATO but this is more about domestic politics than Ukraine joining NATO.

The process of joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has historically taken years for aspiring countries to complete – a process that begins with what NATO calls an “Intensified Dialogue” in which the aspiring country expresses their aspiration to join and sets out to make any necessary political, economic, and/or military reforms required by the alliance in order to meet their membership requirements.

In general terms, NATO members are required to have a democratic system of government based on a market economy; they are required to have a demonstrable record of protecting minorities living in their country; they are required to commit to making a military contribution to NATO and additionally reform their military to meet NATO military standards, and lastly, NATO members must have a military under civil control. Once these requirements have been satisfied and other NATO standards have been met, the aspiring country may be invited to join what NATO calls its Membership Action Plan.

Regardless of how much it may want to, Ukraine is not joining NATO anytime soon – and this is no secret to anyone. While Ukraine engaged in an Intensified Dialogue with NATO back in 2005, the country is still a far cry from adopting the “concrete, measurable progress in the implementation of key reforms and policies” upon which a NATO invitation to pursue a Membership Action Plan would depend.

That was more than fifteen years ago and yet Ukraine to this day has not been invited to pursue a Membership Action Plan. In fact, NATO members very recently stated that Ukraine is not on a track to join the alliance and even now when faced with a potential invasion from neighboring Russia, NATO has ruled out sending its forces to help Ukraine defend itself regardless of years of NATO-Ukraine cooperation since the 2004 Orange Revolution.

Years of close cooperation and partnership between NATO and Ukraine do not equate with NATO membership and so for the most part, Ukraine is now on its own. That the United States and other NATO members are moving troops into the region is not so much to defend Ukraine as it is to defend NATO members located near Ukraine, and although President Biden may have tough words for Vladimir Putin about not invading Ukraine, actions speak louder than words. NATO troop movements mark the real red line not to cross, for Vladimir Putin knows there will be no military response unless his army invades a NATO member. In this way, the United States and NATO have essentially given Russia the green light to invade Ukraine if Russia is prepared to pay the economic price of the promised sanctions.

The big question, considering Ukraine is not on the path to NATO membership and still needs to implement significant, concrete, and measurable reforms before it could even be considered for membership, is why Russia is on the verge of invading Ukraine now. There is no “now or never” situation in which Vladimir Putin sees a Ukraine on the verge of joining NATO and must decide to conquer that country now before it’s too late. Remember: attacking Ukraine after it joins NATO would trigger the alliance’s collective defense provision in Article 5 of its Treaty.

To answer this question, one must look into the current political situation in Russia. After pushing through a laughable amendment to the Russian Constitution in the early months of the pandemic, Vladimir Putin is eligible to run for reelection for a third consecutive term in 2024. Although the Russian Constitution limits presidents to two consecutive terms, his reelection in 2024 will be counted as his first election because the constitutional amendment passed in 2020 “annulled” his previous two terms in office.

When he decides to run in 2024, there is no question that he will remain in office through 2030, and if his health serves him well, run for a fourth (read: second) term in 2030, potentially staying in office until 2036 until the age of 84. Elections in Russia are not conducted in a manner that most people would describe as free, fair, and democratic if only for the fact that political opponents, especially legitimate opponents, are denied ballot access. The candidates who are allowed to run against Vladimir Putin essentially amount to little more than movie extras with casting credits. Some of them might have even been given a script to read.

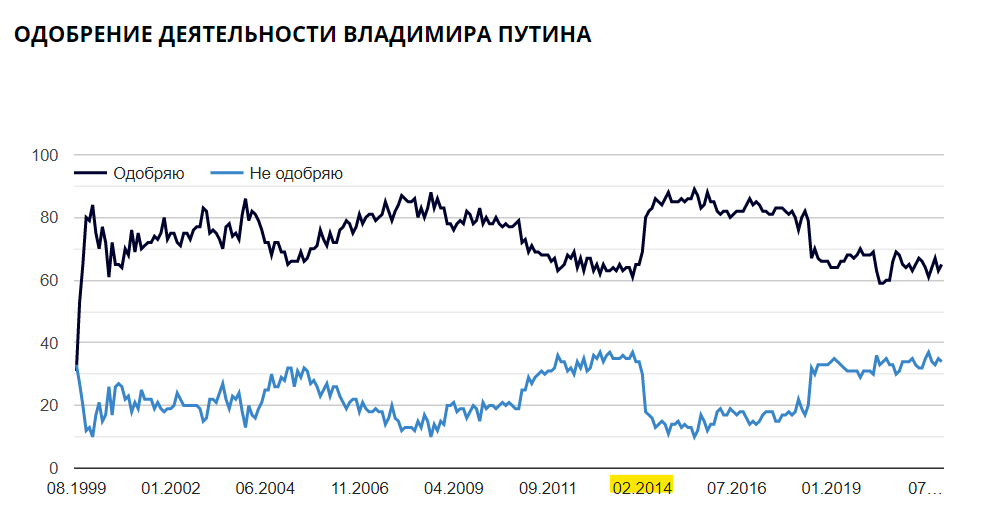

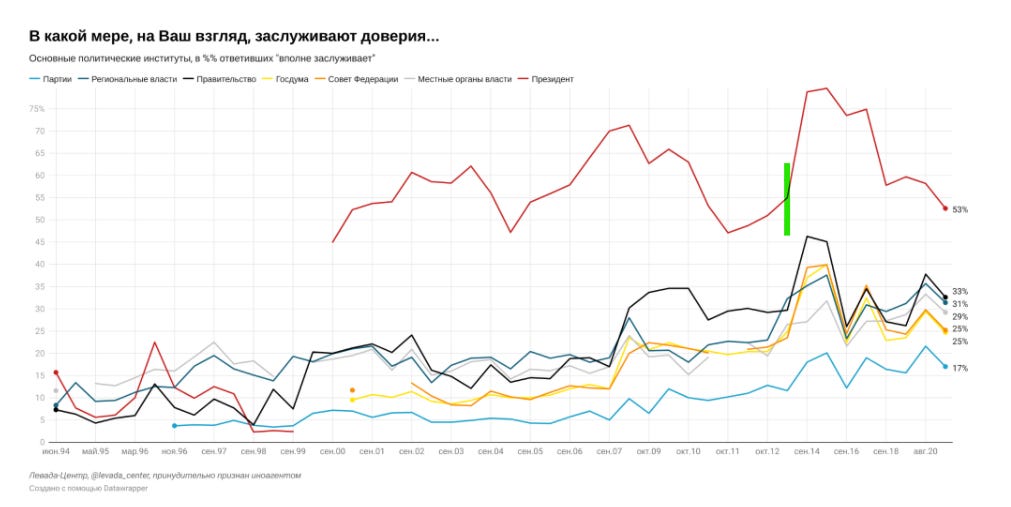

The 2024 election is in the bag for Putin if he wants it, but there are some political considerations to be made. If he plans on ruling into the 2030s, he needs to avoid the appearance of declining support. This is a man whose approval rating has traditionally fluctuated between 65-80 percent. Whether the election results and approval rating are accurate or not is another question. That he won reelection with nearly 78 percent of the vote in 2018 was no surprise – the election results were plausibly possible considering his high approval rating.

The results of the 2018 presidential election represented a spike in support for Putin, who had won reelection six years earlier in 2012 with much less – just 64 percent. Although nearly eighty percent voted for him in 2018, his approval rating today is historically low. A recent survey by the Lambda Center gave him a 61 percent approval rating, continuing a trend of relatively low marks that Putin has been getting since the early months of the pandemic when COVID-related restrictions were put into place. He polled at 65 percent as recently as December.

Granted, approval ratings are not important in a country where elections are not held democratically, but if Putin goes into the 2024 presidential election with public support in the mid 60s as they are now or upper 50s as they were in the early months of the pandemic, a blowout election in which he wins nearly 80 percent of the vote as he did in 2018 won’t be believable. Yet anything less than that will represent a decline in a support exactly when he needs to demonstrate that he is the future Russia – at least until 2036.

In short, Russia is not neighboring Belarus, where the authorities make no effort to even appear to hold democratic elections and have no shame about it. Even though the elections in Russia are also not democratic, they at least on the surface appear to be. So, whatever percent of the vote Putin wins in 2024 has to somewhat correspond to his approval rating at that time in order for him to be seen as a legitimate leader.

What happened between 2012 when Putin won 64 percent of the vote and 2018 when he won 78 percent? Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula of Ukraine. That happened in 2014 and his approval rating skyrocketed, ending a declining trend that had brought him down into the low sixties. Sound familiar? He’s in the exact same situation today.

Putin knows that by invading Ukraine to expand the borders of Russia back into lands that were historically part of the Russian empire, lands to which the Russian state traces its roots, as he did with Crimea, he will feed into nationalist fervor and a sense of pride and patriotism that will again send his approval ratings back up to the roof where they will remain well into 2024. This is the calculation behind the potential invasion of Ukraine, an invasion which would “liberate” the two breakaway provinces of that country known as Donbass that have declared their independence and desire reunification with Russia. This potential invasion has nothing to do with Ukraine joining NATO at some abstract time in the distant future – it is just a pretext for war.

If Putin does decide to tap into national pride to make Russia great again by restoring the Russian Empire, he will do so in spite of western sanctions. The sanctions will supposedly be the toughest in history, but they will likely harm ordinary Russians more than Putin’s inner circle and the oligarchy that control that country. The reality is that Biden’s tough words of historic sanctions further play into Putin’s hands, giving him a foreign boogeyman to blame when the economic situation in Russia worsens as a result of those historic sanctions.

I lived in Russia for over five years and left two months ago. During my time there I visited over a hundred cities, towns, and villages. I can attest to the fact that most of the country lives in modest conditions. Inflation is high and salaries are low. The infrastructure is falling apart. Western sanctions that make conditions worse in Russia are not going to make Russians upset with Putin, they are going to make Russians upset with the West.

From his podium at the annual Victory Day parade later this year in May, Putin, himself an ex-KGB officer, will not only be celebrating the Soviet victory over the Nazis in World War II as he does each year, but he’ll also be able to highlight Russia’s recent victory over Ukraine and the reclamation of lands that were occupied for decades by a “western-backed government” in Kyiv.

He’ll use the opportunity to set the stage going forward. He’ll warn that new western sanctions mean rough economic times are ahead. He’ll insist Russia needs stability and a strong hand at the helm, and that he is that strong hand. He’ll remind the nation of rough times – both in distant and recent history, which they have endured... together, and assure them that they will overcome this new effort to destroy Russia. Now more than ever, he’ll explain, Russians need to stand united as they suffer these western economic sanctions together. Lucky for him, Putin will no longer be the one to blame for the country’s economic problems.

Unless western sanctions are targeted specifically against Putin and his inner circle (for example, by revoking or denying visas to his inner circle and their family members so they can’t vacation in Europe or give birth in Miami or send their children to prestigious universities in the UK or the US), they will only be a tool for him to consolidate support among the masses in the runup to the 2024 presidential election. And that means they are no deterrent to invading Ukraine.

But who knows, maybe he’ll flinch.