With peace borders, national divorce won't divide communities

Partitioning the country between red and blue states isn't the solution but neither is drawing hard borders that divide interconnected urban and suburban areas.

I have been advocating for some form of peaceful political divorce in the United States since I held a rally in Sacramento, California on Valentine’s Day in 2018 calling for a divorce between the state of California and the United States. Politically, my concept of a peaceful national divorce has been somewhat inspired by the so-called velvet divorce that led to the peaceful (thus the moniker velvet divorce) breakup of Czechoslovakia into the present-day Czech Republic and Slovakia, two independent countries that are now military allies and close trading partners.

However, the Czechoslovakian example can only do so much as an analogy for national divorce because our irreconcilable differences are not rooted in geography as much as they were in the case of Czechoslovakia. Also, the concept of national divorce in the United States is still just that — a thought experiment more than anything else, as no campaign exists to actually set such a divorce into motion. Indeed, a consensus has yet to be formed on what national divorce actually means.

If you ask someone like Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, who has been an open advocate of the idea for quite some time already, her take on national divorce seems to be closer to restoring states’ rights in a federalist system. Others advocate a division of the United States along ideological lines, whether it be blue and red states for a more macro-level division, or counties for a more micro-level division. Still others argue for the dissolution of the Union altogether, something which would result in 50 independent countries and turn North America into a western hemisphere version of Europe.

What none of these politicians, pundits and commentators ever discuss, however, are the international borders that a national divorce would create between the several states, or between regions, or counties, or even neighborhoods, depending on where the new borders between the left and right were drawn. There is no simple solution to where to draw the lines, as the cultural and ideological divisions between the left and right are less based on state identity (as was the case during the war between the states from 1861-1865) and more of an urban-rural divide, which is why a national divorce between blue and red states does not go far enough to achieve an ideological divorce between the left and right.

Personally, I belong to the school of thought that suggests abandoning existing state borders and drawing new ones altogether. However, if we were to surgically draw new borders to separate blue and red America, we would have international borders dividing cities and even neighborhoods within cities. That would be a logistical and transportation nightmare, but would it have to be?

If we were to pursue a national divorce and divide the country not by red states and blue states, but more precisely along the urban-rural divide, we could establish "Peace Borders" instead of hard borders. These Peace Borders would allow our highly interconnected urban and suburban areas, neighborhoods, and communities to continue to function as they do now, and they would eliminate the logistical and transportation nightmare of crossing international borders on one's daily commute to and from work, to drop one's children off at school, and on the way to the supermarket down the street. The good news is such Peace Borders already exist for us to draw upon for inspiration.

One of such models can be found on the border of Brazil and Uruguay where the Brazilian city of Sant'Ana do Livramento and Uruguayan city of Rivera straddle the international border between these two South American countries. Together, the two form an "international city” of about 170,000 people. Although the official border between Brazil and Uruguay runs through the middle, essentially dividing the city half, there are no walls, fences or other barriers separating the two halves, and people are free to move about either side of the border while staying within the city.

In a sense, residents and visitors of the city enjoy open borders while there. In fact, the actual border is only marked in a few places. One of such places is International Plaza, a green space in the city center with an obelisk flanked by the Brazilian and Uruguayan flags on their respective sides of the border. It’s a bit of a tourist attraction similar to that of Four Corners Monument where one can stand in Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah at the same time.

However, this Peace Border between Uruguay and Brazil does not mean the two countries have an open border policy — a de facto open border exists for those living, working, or visiting and staying within the city. On one hand, those entering the city from Uruguay with the intent of continuing further into Brazil (or vice versa) must go through the joint border inspection checkpoint located in the city center. On the other hand, those who visit the city from Uruguay but do not travel beyond the city limits into Brazil (or vice versa) would not show their passports, even though they may technically cross into the other country while visiting certain parts of the city.

This could work as a model for the borders we establish between the left and right in the United States through a peaceful national divorce and partition. But a model is only that — a model. We would have to adapt the specifics of how these Peace Borders would apply to our situation and meet our unique needs. However, as a thought experiment, let’s consider how Peace Borders would work after a national divorce between the left and the right in the United States.

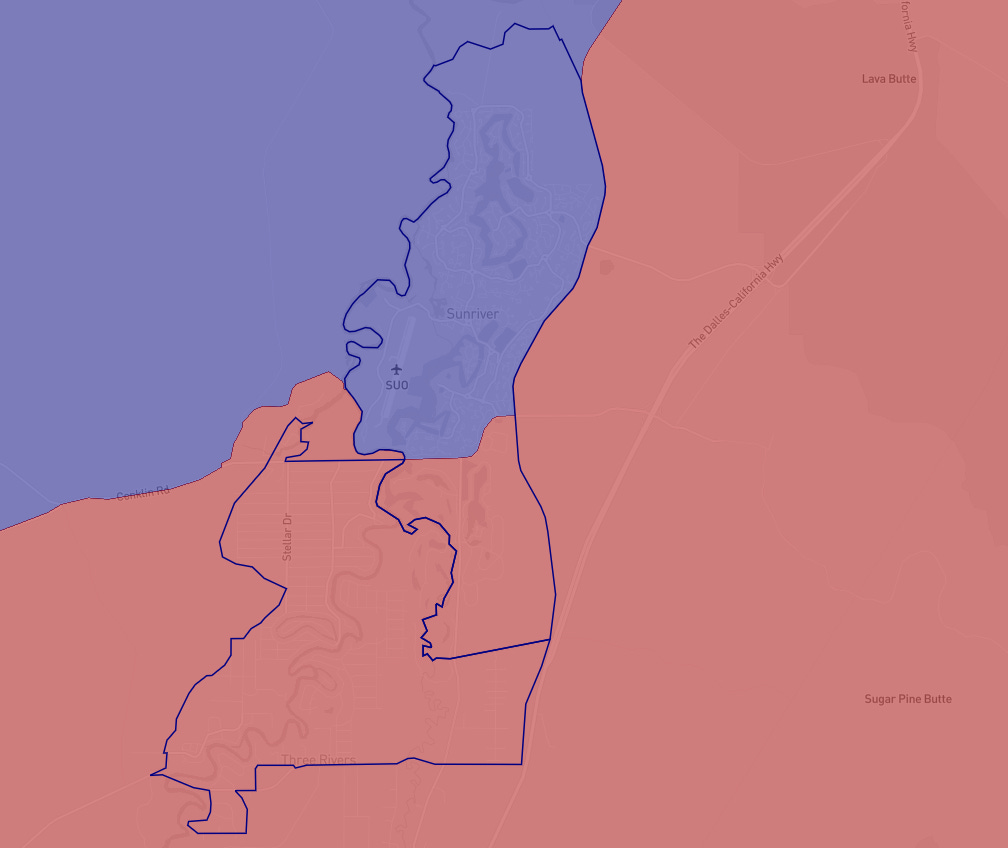

Sunriver (pop. 1200) and Three Rivers (pop. 3500) are two small towns just south of Bend, Oregon. If we were to opt for a micro-level national divorce along ideological lines, the border between the left from right would divide these two small otherwise highly interconnected towns at Harper Bridge, as Sunriver to the north is more left-leaning while Three Rivers to the south leans right. A Peace Border would allow these two municipalities to continue functioning as they do now without barriers to free movement or commerce. However, anyone traveling through these cities from blue America further into red America (or vice versa) would have to stop at a joint border checkpoint, one which could be built next to to the post office in Sunriver.

The result is that residents of right-leaning Three Rivers would still be able to use Sunriver Regional Airport without formally crossing an international border to get there, while residents of left-leaning Sunriver could continue shopping at The Village at Sunriver — a shopping center within Sunriver city limits that falls on the red side of the left/right divide — without formally crossing an international border. Likewise, residents of both municipalities would be able to use the Woodlands Golf Course in Sunriver and the Crosswater Golf Course in Three Rivers without passport checks.

The main problem of national divorce is how to divide red and blue America without tearing communities apart. Peace Borders is a great solution to this problem that not only keeps interconnected communities together, but also reinforces the idea that while the left and right have major political, ideological, and cultural differences, we still have much in common. National divorce is a proposal that allows both sides of the political spectrum to live “under their own roofs” and thus set their own rules, but we don't need to build walls or fences between communities that have lived and worked together for centuries in order to do so.

We can establish traditional international borders with checkpoints and passport stamps between left and right America and Peace Borders, such as the one in Rivera, Uruguay, in those American towns and cities that happen to straddle that border. Doing so will avoid dividing up deeply connected and interdependent communities.